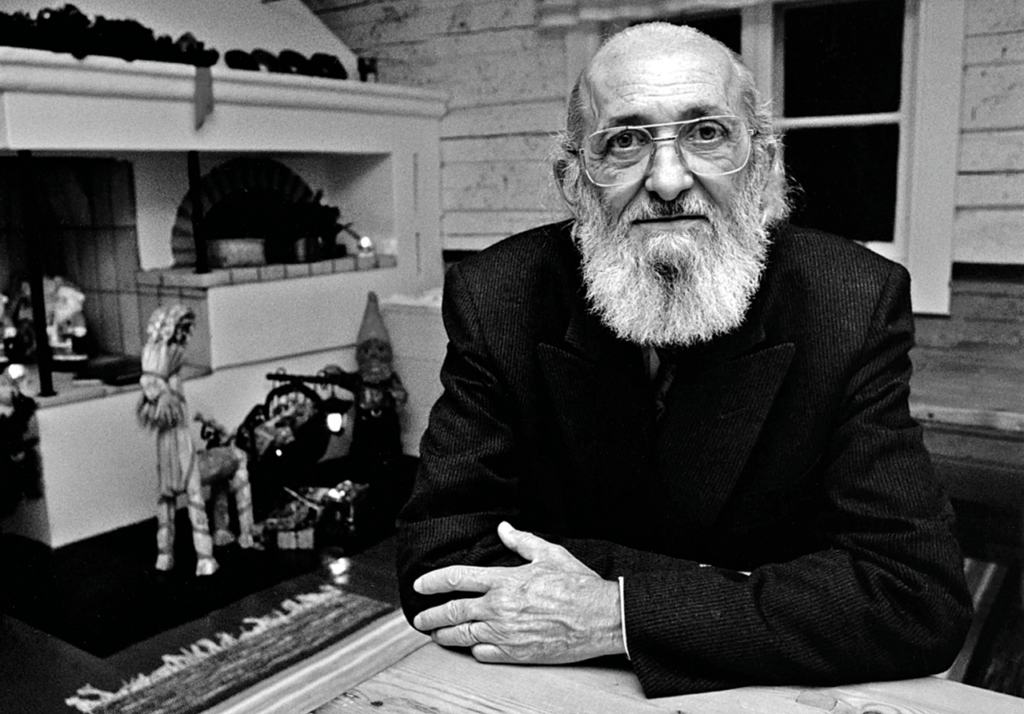

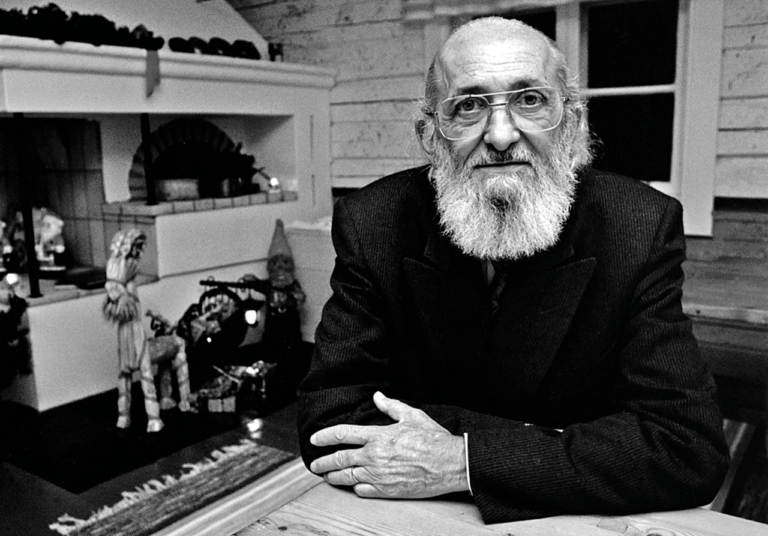

Author of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Brazilian educator Paulo Freire is as controversial as ever.

September 19, 2021 marks the 100th anniversary of Paulo Freire’s birth, Brazilian educator known worldwide as founder and advocate of “critical consciousness,” a forerunner of critical pedagogy. Two years ago, the golden jubilee of his bestseller, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968), was commemorated in Brazil and elsewhere as Freire’s work found in many countries a fertile ground to germinate and take root.

From his hometown Recife, in northeastern Brazil, to countries like Chile, Zambia, Tanzania, Guinea-Bissau, and Angola, where Freire developed adult literacy programs, his call for radical social transformation through education has been deeply influential in a wide range of fields, from education to sociology and community development.

For Freire, education is either a form of emancipation or an instrument of oppression. As such, he argued a pedagogical approach should be developed with the students, rather than for them, especially those who come from marginalized populations.

Freire’s model encouraged students to critique the educational and political systems by emphasizing the connections between individual struggles and social context.

Born to middle class parents, his father’s death in 1929, during the Depression, impoverished his family. As he recalls in Moacir Gadotti’s book, Reading Paulo Freire, “I didn’t understand anything because of my hunger. I wasn’t dumb. It wasn’t a lack of interest. My social condition didn’t allow me to have an education. Experience showed me once again the relationship between social class and knowledge”.

Growing up living among poor rural families and laborers greatly influenced Freire’s philosophy, pedagogy, and politics. He became a grammar teacher while still in high school. In college he participated in Catholic Action, a religious organization that challenged laypeople to express their faith through acts of service, especially to the poor. This challenge and experience motivated Freire to develop adult literacy programs in northeastern Brazil.

Freire expressed his ideology as equal parts Jesus Christ and Karl Marx. Although he often demonstrated frustration with the institutional church’s failure to participate in revolutionary movements, he maintained close ties with many Catholic clergy, particularly those associated with Liberation Theology.

His left wing politics played a significant role in the history of Brazil. In 1963, he served in João Goulart’s center-left government as the president of the National Commission on Popular Culture. The committee introduced an educational campaign that planned to use Freire’s teaching methods to bring literacy to 5 million Brazilian citizens. At the time, literacy was a requirement for voting, and Goulart hoped that Freire’s campaign would increase electoral participation.

In 1964, the Brazilian military overthrew the Goulart government in a coup d’état and arrested Freire. During his trial, one of the judges accused him of plotting to transform Brazil into a communist state and Freire was imprisoned for 70 days before he received political asylum in Chile. He spent sixteen years in exile, including a year as a visiting professor at Harvard and ten years as an education advisor to the World Council of Churches.

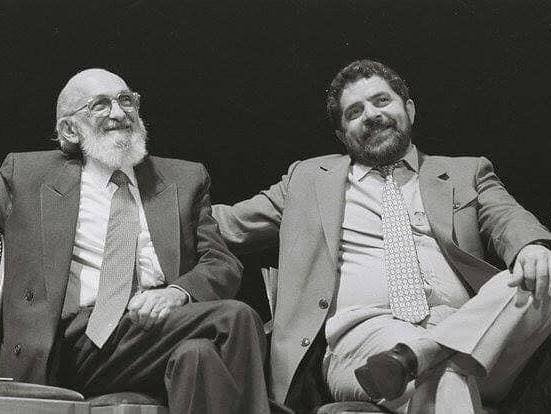

Freire returned to Brazil in 1980, where he taught at the University of Sao Paulo and became one of the founding members of the Workers’ Party (PT) with Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. The educator supervised many of the PT’s adult literacy projects and served as municipal secretary of education in Sao Paulo between 1989 and 1991.

Paulo Freire died of heart failure at the age of 75 on May 2, 1997. His philosophy and legacy helped to elect President Lula in the 2002 general election, making him one of the international left’s most beloved icons.

During this time, Federal funding for education increased substantially – The Ministry of Education (MEC) nearly tripled its budget and the National Fund for Basic Education (Fundeb) was created. Access to basic education was universalized and reinforced by social programs’ requirements such as Bolsa Família (a state-funded pension to families living under the poverty line provided their kids were enrolled and attending schools as well as vaccinated).

In 2012, Lula’s successor President Dilma Rousseff signed into law making Paulo Freire the official patron of education in Brazil. Rousseff’s decree has set off a firestorm of criticism, especially after Jair Bolsonaro’s victory in the 2018 presidential election.

The controversy around Freire’s influence has become a topic of heated national discussion as the Brazilian right-wing blame his ideas for the failure of Brazil’s education system, using cultural Marxism to indoctrinate children.

Critics also point out Freire’s social theory as often illogical and inconsistent, which rarely presents evidence of an empirical nature or cites sociological research for his analysis. Consequently, it tends to present a simplistic and optimistic view of the actual possibilities of socio-political transformation. The Marxist influence certainly does not help to correct these appreciations as it often contradicts Freire’s own Christian ethics.

Also, currently having Freire as its patron of education, Brazil ranked 57th among the 77 countries participants on the latest PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), released in 2018. Only 2% of students in Brazil performed at the highest levels of proficiency (Level 5 or 6) in at least one subject, and 43% of students scored below the minimum level of proficiency (Level 2) in all three subjects. Internationally, there are critics about the results of his education in countries like Puerto Rico and Guinea-Bissau.

However, over the years, more people have become interested in Freire’s work, particularly in the United States. According to publisher Paz e Terra, sales of Pedagogy of the Oppressed increased by 60% in the first half of 2019 compared to 2018.

On September 19, Google featured Doogle on its homepage for celebrating Freire’s centennial, along with numerous people and organizations worldwide demonstrating both support and opposition to his ideas. However, being free to deliberately provoke debate is at the core of Paulo Freire’s philosophy: “If the structure does not permit dialogue the structure must be changed”, he said.

Obrigada, Paulo Freire!

Visit freire.org